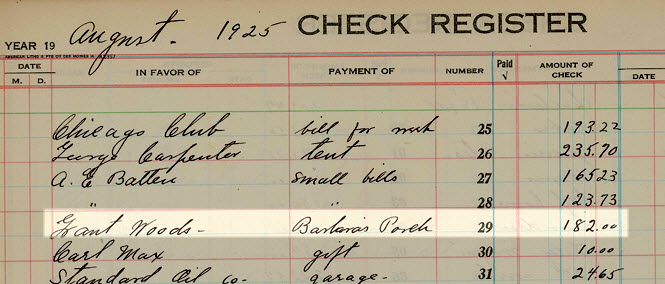

In 1925, Irene Douglas paid Cedar Rapids artist Grant Wood $182 to design and install a sleeping porch for her daughter’s bedroom. Sleeping porches were viewed as a healthy way to connect with the outdoors and offered relief from hot summer nights in home without air conditioning.

Although Irene had discerning taste and could afford art from all over the world, she frequently chose to support local artists. Grant Wood went on to earn international acclaim. Today, his American Gothic painting, created in 1930, is the third most recognized portrait in the world.

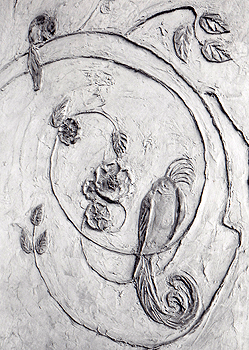

Decorated in a plaster relief depicting curving vines, flowers, birds, and animals, the Grant Wood Porch offers a unique opportunity to see the artist’s versatility and skill.

The personal connection between the Douglas family and Grant Wood’s early career is underscored by the fact that from 1924 to 1935, Wood’s studio at 5 Turner Alley occupied the building that originally served as the Douglas family’s carriage house. The Douglases lived at the house on 2nd Avenue and 8th Street SE before moving to Brucemore in 1906. Irene’s passion for the arts made this rather incidental association more powerful.

The most committed and generous of Grant Wood’s patrons was David Turner, a successful mortician and civic booster. In the mid-1920s, Turner encouraged Wood to begin supporting himself solely through art and freelance interior design projects. Wood crafted interior details and décor that still survives in Brucemore and other local homes.

From landscapes with rolling farm fields to depictions of American folktales, Grant Wood’s best known works of art observed the world and community he understood so well.

Cedar Rapids, where Wood lived and taught for much of his life, is home to a unique collection of his masterworks, as well as a large assortment of architectural details designed by the regional artist. Historians credit Wood with the design and installation of fireplace screens, leaded-glass windows, murals, and more throughout the community. Located in private homes, few of these are available for the public to see. Wood’s mural at Brucemore is one of the few examples in its original setting and available for public viewing.

Conserving the Grant Wood Sleeping Porch

In 2012, the Brucemore Board of Trustees and staff made the conservation of the Grant Wood Porch an institutional priority. Years of assessing the piece, documenting environmental conditions, and addressing the surrounding structural needs laid a critical foundation for this important project.

In February of 2013, Brucemore hired Tony Kartsonas of Historic Resources, LLC (Wisconsin), to lead the conservation project. Other experts joined the team throughout the process, including fellow conservators Susan Goione Buchholz (Colorado) and Richard Wolbers (Winterthur/University of Delaware), architectural engineer Mark Nussbaum (Chicago), and the 3-D laser scanning firm CARMA (Texas).

This conservation project was made possible through grants from the National Trust for Historic Preservation, state of Iowa, and Greater Cedar Rapids Community Foundation; and private donations from the community.

Grant Wood coated the masonry sleeping porch in a plaster relief, crafting stylized woodland animals playfully situated on vines climbing the walls. The mural is exceedingly rare and is the most important work of art in the Brucemore collection.

Originally exposed to the harsh winters and humid summers of eastern Iowa, the National Trust for Historic Preservation enclosed the porch for the first time shortly after Margaret Douglas Hall bequeathed the property in 1981. However, water continued to threaten the piece as rain leaked down an interior wall and moisture seeped through the brick wall. Rehabilitation projects in 2008 and 2012 addressed these issues.

Photo courtesy of MultiVista

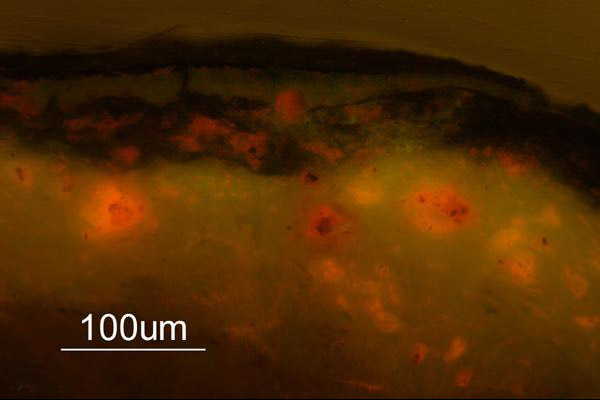

Environmental conditions forced the binding material (oil) of the paint into the plaster, leaving the pigment floating precariously on the surface. Photomicrographs of a sample under blue excitation show the oil resin binder (in orange) seeping into the plaster.

Photo courtesy of Historic Surfaces LLC

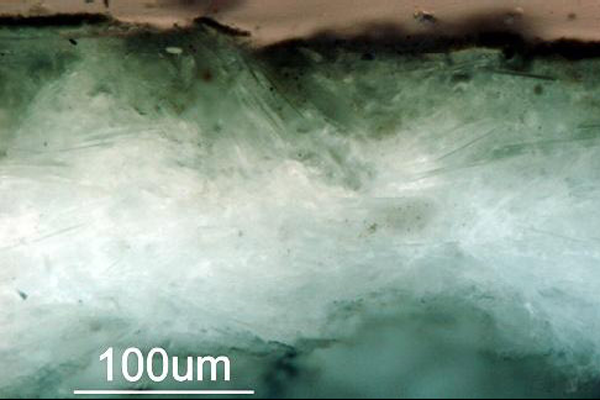

Wetting and drying cycles re-crystallized the gypsum plaster. According to conservator Anthony Kartsonas, Historic Surfaces LLC, this may have been a fortuitous accident that kept the paint securely in place—the crystallization held the pigment in place on top of the plaster. Otherwise, the color of the piece might have been completely lost forever. The photomicrograph of a sample in violet light reveals the re-crystallization.

Photo courtesy of Historic Surfaces LLC

Lightly vacuuming and dusting the mural has uncovered rich blues, greens, and lavenders previously covered by dirt. This basic process produced better results than the conservators expected. Although subtle and still blanched, hints of color emerge on this previously gray bird.

Conservators applied a dilute solution of Avalure, a polymer currently being used in masonry conservation, to consolidate the crumbling plaster. Avalure is an excellent conservation material because the effects are reversible with slightly alkaline water. It does not trap moisture and it has a very low surface tension. The polymer will saturate and consolidate the plaster leaving the pigment and dirt at the surface. Conservators have consolidated the plaster in the lower half of the image while they have only vacuumed the upper half.

Conservators from Historic Surfaces LLC stabilized and cleaned the delicate surface to reveal more vibrant and deeper colors over the course of the summer. In many cases, the effects of sun-blanching and pollution were reversed. This project was not considered a restoration because minimal in-painting and surface recreation occurred.