Domestic servants were integral to every part of the Brucemore estate. During the years the Douglas family made Brucemore their home, at least ten servants were employed at any given time to clean the house, care for the children, cook the meals, maintain the grounds, greet visitors, wash and iron clothing, and a variety of other duties.

The hired help supported the family’s lifestyle and allowed the Douglases to pursue recreational hobbies, artistic work, and community service. In the nineteenth- and early-twentieth-centuries, many live-in domestic servants worked for wealthy and middle-class families.

With the lady of the house freed of house work, she was able pursue cultural activities and become involved in her community. Most families employed one servant known as a “maid-of-all-work.” In Cedar Rapids, a small number had two servants, and an exclusive group hired three or more servants.

The Douglases, a family of five, employed one or two maids, a butler, a cook, a nanny, a coachman or chauffeur, and a head gardener who supervised five to eight men on the grounds. Although the Brucemore staff was quite sophisticated for Cedar Rapids, it was small compared to those of their peers in other areas of the nation.

Like other large homes built in the 1880s, the Brucemore mansion had clearly defined areas for family and staff, including separate entrances, dining areas, bathrooms, and staircases. Concealed workspaces and living quarters made the servants virtually invisible to the family and their guests. Designed to be simple and functional, the servants’ side allowed for the most efficient use of an employee’s time.

Servants working for the Douglases and other families across the country were expected to follow a strictly defined behavioral code and standard of work. They were required to be neatly dressed, polite, and maintain a calm disposition at all times.

Workdays were long as hired help would wake up before the family to clean the main rooms of the home, prepare breakfast, and serve family members as soon as they awoke. A servant’s day would continue until the family retired for the night.

Due to the long hours, housing was provided for essential staff. Servants working inside the house (maids, butler, and cook) generally lived on the third floor of the mansion.

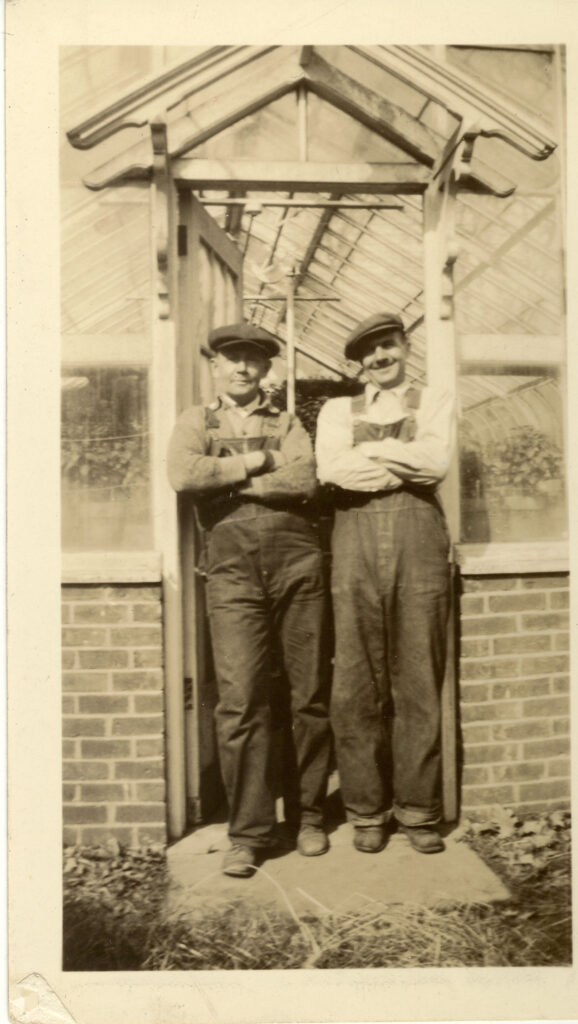

The head gardener and house staff with families lived onsite in the Servants’ Duplex. The Duplex was part of a small “village” that consisted of support and recreation buildings, including a greenhouse, barn, chicken coop, and squash court that later served as a bookbindery.

The Servants’ Village, located on the east side of the Brucemore estate, provided living and working space necessary for the Douglas family’s servants to maintain the property.

Designed to be functional, the Servants’ Village was set apart from the side of the estate enjoyed by the family. The buildings were accessed by a separate road so the hired help did not need to use the main entrance. A wall of hemlocks blocked the Servants’ Village from view, while the green and brown building colors caused them to blend into the landscape.

Meet the Staff

Caroline Sinclair employed several servants both before and after she built “Fairhome.” As a widow, mother of six, and active community volunteer, she needed the help of several employees to maintain her estate. This c. 1880 photo shows four women employed by Caroline. The seated woman, Elizabeth Brown, was employed by the family for many years.

One of the first servants an upper-middle class family would choose to employ would be a Cook. Cooking for a household was a time-consuming task at the turn of the century with few labor-saving conveniences. This unidentified person was likely a cook for the Douglas family at their previous residence, 800 2nd Avenue.

Ella “Danny” McDannel was hired by the Douglas family shortly after Barbara’s birth. As a trained nurse, Danny had worked for other socially prominent families in Cedar Rapids prior to working for the Douglases. Danny held a special position within the family. After she was no longer needed as a nanny, she was employed as a personal assistant to Irene Douglas, frequently traveling with her. She left the Douglas family to marry in 1930. The family kept in touch with Danny until she passed.

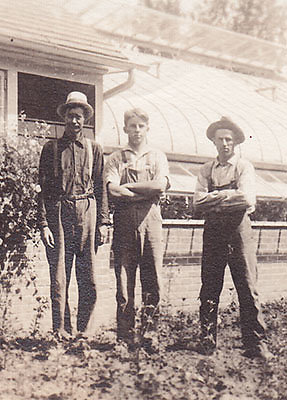

Archie White was another one of the Douglas family’s longest tenured servants. Archie was the head gardener from 1921 to 1937. He worked closely with Irene Douglas in executing her vision for Brucemore’s landscape. He and his family lived in the Servants’ Duplex where he and his wife raised their two children, Edward and Agnes.

Howard and Margaret Hall lived less formal lives than the Douglas family a generation prior. They employed fewer servants with broader duties. Nial Dicken served as the Hall butler for many years, though his duties also included serving as a chauffer and helping care for the family pets. Carolyn Shimek (center) began working as the Hall’s maid. Sylvia Podhajsky (right) was employed as a cook. Both Nial and Carolyn still worked for Margaret when she died and were given life tenancy in the Servants’ Duplex and Bookbindery, respectively.

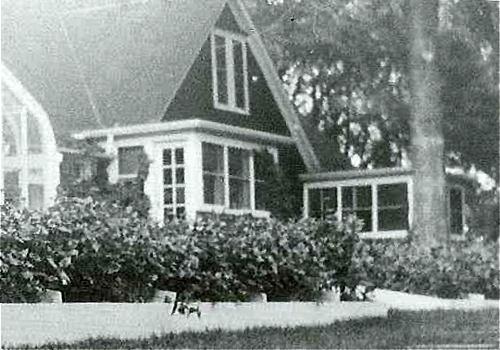

In 1909, the Douglases built this duplex for married servants and their families. The two sides are mirror images, each with a kitchen, dining room, parlor, two bedrooms, and a bathroom. Separate housing offered privacy, but kept workers within summoning range.

Danny the Nanny

One employee, Ella McDannel, had a very close relationship with the Douglas family. Fondly named “Danny the Nanny” by the Douglas girls, Danny worked for the family for over 20 years.

An American-born woman, she was the same age as Irene and had a nursing degree. The Douglases hired her in January of 1909, one month after Barbara’s birth. Her bedroom was on the second floor next to the nursery and her primary duties involved caring for the three girls.

In her diary, she documented their milestones, illnesses, birthday parties, sleepovers, and other events, as well as her daily activities and those of other servants. Danny’s diary suggests that the staff shared some duties even though most multi-servant households were very specialized.

Her other tasks included washing Irene’s hair, cleaning, dusting, mending, and sewing. The second longest standing employee, she left the family by 1930, but remained in contact with them for the rest of her life.

Social and cultural changes

The Douglases lived in a time when changes in society and culture made hiring, managing, and keeping servants more difficult. Although domestic service often paid better than factory or department store work, the lack of personal freedom, unpredictable and long hours, and social stigma discouraged women from taking these positions.

As a result, employers frequently turned to immigrants and minority populations as a source of help. By the 1920s, the servant pool became even more limited due to World War I and immigration restrictions.

While middle class housewives stopped hiring live-in servants in favor of new household appliances and day workers, wealthy families continued to hire live-in servants to illustrate social status and maintain their larger homes and estates.

Iowa, like other Midwestern states, had smaller servant populations than the Northeast and South. In Linn County, many Bohemian and German immigrants, along with American-born girls, worked as servants. Having male servants signified a high social position; therefore, men generally filled positions that required them to be visible to family and guests such as the butler or chauffeur.

The lives of individual servants often can be difficult to trace. In some cases, city directories and census records may provide the only source of information. Fortunately, the stories of several servants at Brucemore have been preserved through sources like diaries, photos, letters, account books, and other documents.