Across the country, changes in technology created opportunities for new industries. In Cedar Rapids, the proximity to agricultural products allowed producers to purchase the supplies needed and the rapidly expanding network of railroads made the distribution of products easier.

George and Walter had seen their father benefit from these changes. George Douglas Sr. had immigrated from Scotland to the United States and began a career working for the railroad builders in Iowa. After building railroads, George Sr. put them to use. He started a cereal company with Robert Stuart, producing oatmeal and other cereals. In 1891, this company merged to become The Quaker Oats Company.

Having seen their father found a successful company, George and Walter Douglas set out to start their own. The brothers partnered in 1894 to form Douglas & Company and began producing linseed oil. They operated the company until 1899, when they sold the business to the American Linseed company.

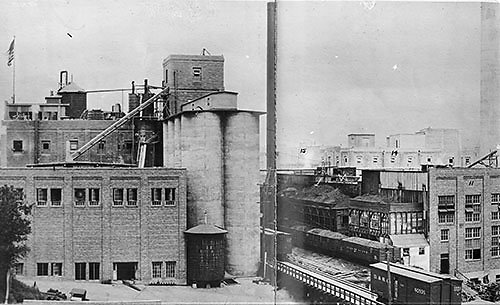

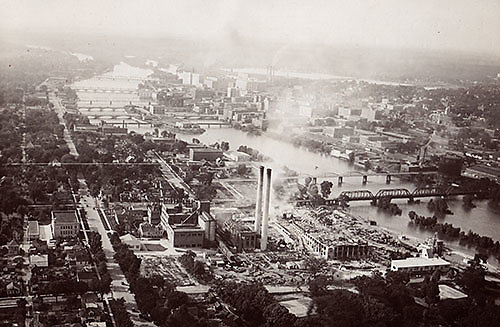

Not long after, the brothers were looking for their next venture. In 1903 they started the Douglas Starch Works. This enterprise produced cooking starch and oil, laundry starch, animal feed, soap stock, and industrial starches. By 1914, the Douglas Starch Works had become the largest starch company in the world, and by May 1919, the company employed more than 650 people and produced 20,000 bushels of corn per day. The Starch Works plant was located on the banks of the Cedar River and consisted of 36 buildings on ten acres of land.

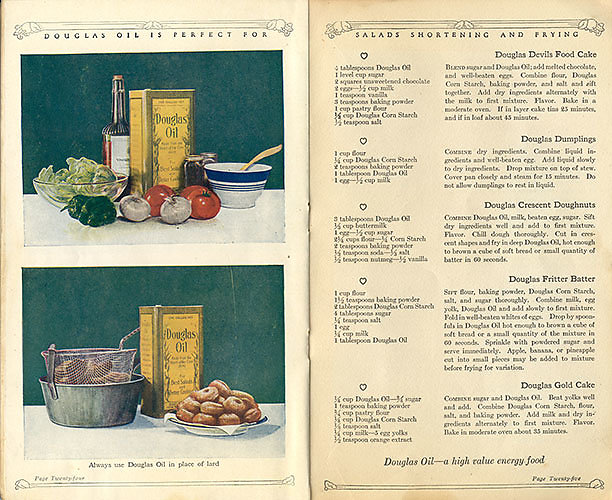

Rationing during World War I increased the demand for corn products as an alternative to butter or lard. The U.S. Food Administration encouraged substituting corn for wheat products, increasing the company’s revenue. Corn oil and cornstarch became essential cooking items for homemakers, bakers, and cooks who used them to make puddings, pie fillings, sauces, and baked goods. Millions of potential customers could see Douglas & Company products in Good Housekeeping, The Ladies’ Home Journal, and The Saturday Evening Post.

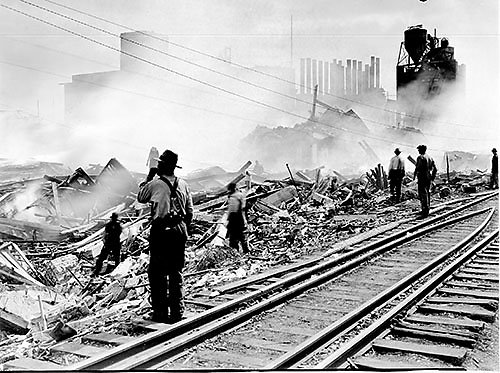

The Douglas Co. Starch Works

Destroyed by Explosion & Fire May 22nd 1919

The Explosion that Shook the City

On Thursday, May 22, 1919, work proceeded as normal throughout the day. A starting box malfunction at 5:45 PM, delayed a few workers leaving the day-shift, but generally business progressed as usual. Workers on night-shift took their places and those from the day-shift made their way home. Suddenly, an explosion boomed.

Workers were sent into confusion. Joe Toman, a mill-wright, saw clouds of smoke and heard a terrific sound before seeing parts of the building flying from the force of the explosion. J. Livingston was standing on a bridge spanning the Cedar River and was knocked down by the force of the explosion. Oscar McShane was in his home across the river from the plant at the time of the explosion. When he heard the noise, he ran outside and saw timbers flying from the site.

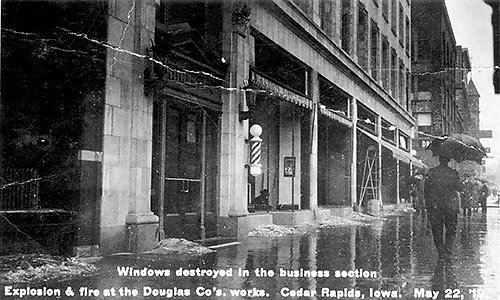

Across the city, community members did not know what to think. People in the business district of Cedar Rapids were shocked as glass flew from windows and shattered around them. In a neighborhood across the river from the plant, a young child was thrown from a couch and died. People reported that the blast was so strong that they thought the explosion had come from inside their homes. Others were convinced the city was being attacked (the explosion occurred just six months after the end of World War I).

George Bruce Douglas, the president and co-founder of the company, was at dinner with his wife, Irene, when the explosion occurred. George rushed to the scene and joined first responders in preparing a plan for rescuing the injured.

Irene, expecting the worst hurried to their home, Brucemore, and began the process of converting it into a hospital. She feared that the number injured would exceed the capacity of the local hospitals. These fears proved to be unfounded; the rescue efforts were just beginning to uncover the scope of the damage.

The fire made initial efforts to move debris difficult. Once extinguished the residual heat and the scope of the damage slowed the recovery and it was several weeks before all rescue efforts were completed. In total, 43 men lost their lives at the plant and thirty more were injured.

But even as the rubble was being cleared, rebuilding began, and out of the explosion grew a collective, community experience. Just two days after the accident, the following appeared in a local paper:

The explosion at the starch works occupies all our thoughts today. As one goes in and out among the people it is interesting to note what phase of it lies close to the consciousness of different types of men. With some it is the thought of business consequences, loss, removal, commercial advantage and disadvantage; with others the thought is of the unknown dead, still to be drawn from the hot ruins: others think of the homeless and fatherless and crave to be shown how to help. Yet at the bottom of all the talk there is deep sympathy- whether it is for money, loss, or sorrow or suffering. One thing may reconcile us to being human even when we are most tempted to be disgusted with our kind- it is the essential compassionateness of man.

Businesses replaced windows and made other repairs, eventually re-opening. The Cedar Rapids Chamber of Commerce established two committees to aid in rebuilding.

One committee focused on assisting families who lost loved ones or whose homes were damaged. In total, 218 homes were damaged by the explosion, with others sustaining minor harm.

The other committee turned its attention to rebuilding the Starch Works plant. With more than 650 employees, the Starch Works played an important role in the economy of Cedar Rapids. Hundreds of families were considering the prospect of unemployment. Corn suppliers were facing the loss of a major purchaser.

[The Douglas Starch Works] is a great institution, employing large numbers of people, adding to the manufacturing output, the bank deposits and clearings and the general commercial life of the city. Cedar Rapids wants the starch works to be rebuilt here.

June 23, 1919 CR Evening Gazette.

As insurance claims and investigations progressed, Douglas & Company was able to stay afloat. In February of 1920, nine months after the explosion occurred, Douglas Starch Works was sold to Penick and Ford. A major win for the Cedar Rapids economy, this purchase allowed Cedar Rapids to retain an important industry and double the number of employees at the plant to 1,400.

Through company changes since, the industry started by the Douglases continues to be an important part of the local economy in the 21st century.

Explore the Impact of the Explosion

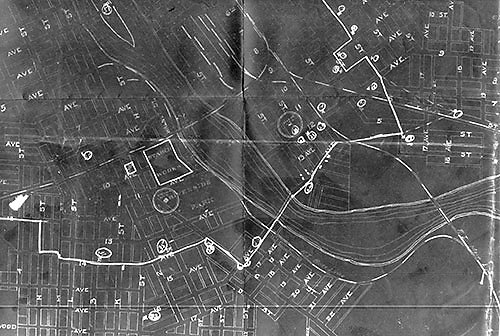

On May 22, 1919, a small fire at the Douglas Starch Works created an explosion resulting in one of the worst industrial accidents in Iowa history. When the explosion boomed at the Douglas Starch Works plant in 1919, people around Cedar Rapids felt the blast. Homes lost shingles and windows were blown in. Buildings were damaged and shops were closed. Households experienced loss as 44 people died.

Explore how the explosion impacted locations across Cedar Rapids by clicking on the map below:

The locations indicated on this map are based on the U.S. Department of Agriculture report, local newspaper accounts, and Sanborn maps.

Videos

Watch community leaders, scholars, and staff reflect more than 100 years later on the tragedy of the Douglas Starch Works explosion and the ways it shaped Cedar Rapids.